Table of Contents

Exploring Violent Encounters with Police

through Data Visualization

4.1: Police Violence

Frequency by Age and Race

4.2: Police Violence

Frequency by Age and Race and Armed Status

4.3: Police Violence

Frequency by Mental Health Category

4.4: Police Violence

Frequency by Armed Status

4.5: Police Use of Body

Cameras in Violent Incidents

4.6: Charges Brought

Against Police after Violent Encounters

Exploring Violent Encounters with Police

through Data Visualization

Aaron Davis

University of Colorado at Boulder

M.S. in Data Science

December 3rd, 2022

Part 1: Context Definition

Use of violence by police in the United

States is a timely topic, particularly given the death of George Floyd in May

2020. Tragedies like these must drive a

critical examination of use of force by police in the US. Solutions cannot be offered unless the

problem is understood thoroughly. The

motivation of this project is to identify concerning trends in use of police

force so that corresponding solutions for each concerning trend can be

proposed. The goal is to ultimately

reduce use of police force, because we can all agree that less violence is

better.

Exploring this problem is particularly

important because people too often let issues divide them across political

party lines when the issues in question have real and dramatic impacts on

people and their families lives and legacies.

Police violence is one of these issues, and we ought to be working our

absolute hardest to minimize all violence to prevent unnecessary physical and

mental harm to people who have encounters with the police. Follow the data, not a party line.

Part 2: Question Definition

The goal of this exploration is to

develop insight on what factors police departments in the US should focus on

handling better - whether that means improving mental health services, for

example, or focusing on recognizing and decreasing discrimination against

protected groups.

Specifically, we’re answering the

question “what trends in use of force by police in the US appear to be

problematic?”. To be clear, our goal is

not to provide solutions in this report.

Instead, we’re working to ensure that we really intuitively

understand the problems represented in the data so that the next step of

identifying practical and efficient solutions can be done.

Part 3: Methodology

MappingPoliceViolence.org

provides an automatically updated dataset that includes police violence records

from 2013 up until recent months (most recent datapoint is from 8/8/2022, as of

9/29/2022) in the USA. With over 10,000

records from the last 9 years, this dataset seems to be very comprehensive,

both in terms of number of records and number of features. Features of interest in this dataset include

victim age, gender, race, date of death, location of incident, and cause of

death. There are also additional

features that may be of interest when trying to identify and report on

concerning trends.

The first step we plan to take is to

clean the data by removing features that aren’t conducive to creating

visualizations, like the “circumstances” feature which provides a plain text

description of the circumstances surrounding the incident. We’ll also remove features that contain

easily identifiable personal information, like victim name, photo, or news

article links.

Next, we want to select features that

have a low percentage of missing values.

If we skip this step, then our final results

may be inaccurate if certain subsets in our population have disproportionately

higher missing value count for certain features than other subsets of the

population do.

Third, we will calculate information

like correlation between features. While

this information will not appear in this report, it will be useful in helping

us decide which plots might have the most interesting results to show. This step is helpful, because we don’t just

want to show plots… we want to show insightful plots (i.e.

plots that show some unexpected pattern or provide confirmation for an expected

pattern).

Finally, we will create plots. Our plots will likely be focused on count

data (summarizing number of people with known mental health issues who have

died in incidents with police, for example), or proportion data (for instance,

what percent of the total number of violent run-ins have been with a particular

race, as compared with the percent of the total population of that area that

race makes up).

Part 4: Insights

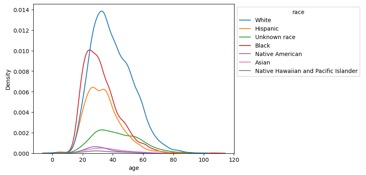

4.1: Police Violence Frequency by Age and Race

In the plot below, we see that density

of police violence when broken out by race appears to peak earlier for black

people than for people of other races.

This seems to indicate that younger black people are at more risk of

police violence relative to people of other races. A similar but slightly less pronounced trend

exists for younger Hispanic people.

Figure 1: Age of Victim Broken Out by

Race

Is this trend an indication of racial

bias in use of force by police? We

provide insight into the answer for this question by breaking this plot out

further by the reported status of whether or not the

individual who experienced police violence was armed during the incident. (Legend from this plot carries over to all

other plots broken out by race.)

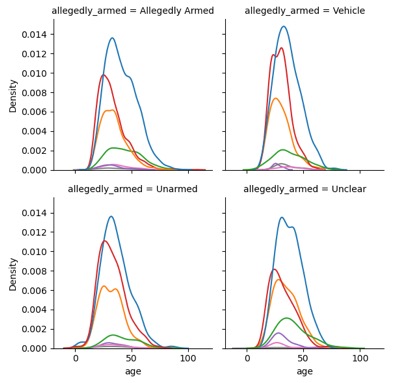

4.2: Police Violence Frequency by Age and Race and Armed Status

Figure 2 appears to show that the bias

towards black people experiencing police violence at a younger age relative to

other races is independent of whether the victim is armed, unarmed, or whether

it is unclear. In other words, police

violence towards younger black people does not seem to be dependent on

variation in whether or not the victim is armed. Racial bias, then, seems like the most

reasonable likely next explanation. This

discovery ought to shift the focus towards recognizing and removing racial bias

in police departments across the nation.

Figure 2: Figure 1 Broken Out by Armed Status

We’ve seen from figures 1 and 2 that

there seems to be a relationship between race and age of violent encounter,

particularly for black people in the US, and this relationship does not seem to

depend on whether the victim is armed, so (to reiterate) the next reasonable

step would be to examine racial bias in US police forces.

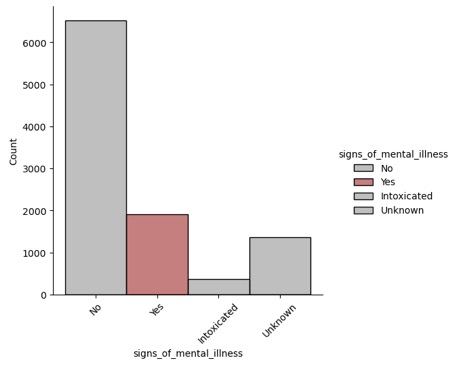

4.3: Police Violence Frequency by Mental Health Category

What about the relationship between

violent encounter with police and mental health of the victim? Figure 3 shows a

concerning trend. Mainly, the

visualization appears to show that almost 20% of the violent encounter in our

dataset occurred with people with apparent signs of mental illness.

Could these violent encounters been

prevented if each police department had allocated more funds towards training

officers in how to deal with different mental health conditions? This analysis will not answer the question,

but it does show that the question is extremely relevant to significantly

reducing overall count of violent encounters.

Figure 3: Count of Victims in Each

Mental Health Category

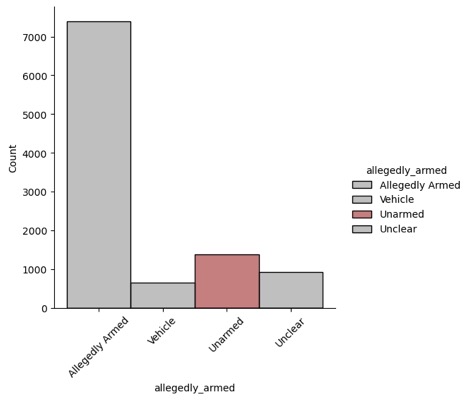

4.4: Police Violence Frequency by Armed Status

In this next plot, we see that a large

portion of the victims of police violence in the past 9 years have either been

unarmed or it has not been clear that they were armed. These two groups appear to compose

approximately 20% of all deaths by police violence. This is again an extremely concerning

trend. It is possible in some situations

that violence needs to be met with violence to help keep the public safe but

using violence against unarmed civilians seems to be a questionable practice at

the very best, and at worst an egregious misuse of power by a someone who ought

to be a public servant.

Figure 4: Count of Victims in Each

Category of Armed

This trend seems to

indicate that another significant opportunity to reduce violence in police

encounters is to spend funding focusing on ensuring officers’ assessments of

the threat level in given situations match the actual threat level. A very small fraction (obviously zero is

better) of violent encounters with police should be with unarmed civilians, and

when a number that should be close to 0% is close to 20% there’s a clear

problem that needs to be fixed.

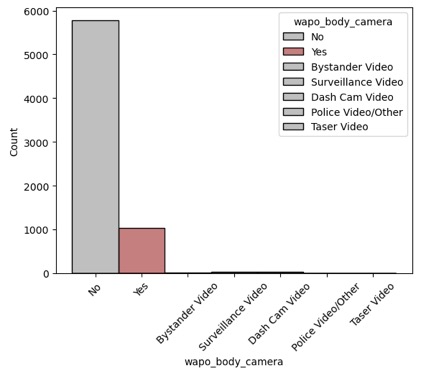

4.5: Police Use of Body Cameras in Violent Incidents

How frequently are violent encounters

recorded? This question is particularly

important because having recordings of violent incidents is in the best

interest of anyone interested in knowing exactly what happened without the

subjectivity inherent in reviewing witnesses.

Figure 5 shows another rather concerning trend.

Figure 5: Count of Recording Category

We see here that around 85% of violent

encounters are not recorded at all.

Around 15% of violent encounters are recorded on police body cameras,

and a very small percentage of recordings come from other sources. And this is only the subset of the data that actually recorded whether or not a body camera was

used. This plot seems to show an issue

with lack of objectivity in data about what actually happened

in violent incidents, because recordings are the closest thing we could have to

objective evidence, currently.

This problem could either be rooted in

a lack of body cameras for police departments (which can be fixed with better

funding allocation), or it could be rooted in lazy or malicious misuse of body

cameras, which ought to be disciplined.

Again, our goal in this report is not to identify solutions, but rather

we’re trying to understand the roots of the issues the data shows about violent

police encounters.

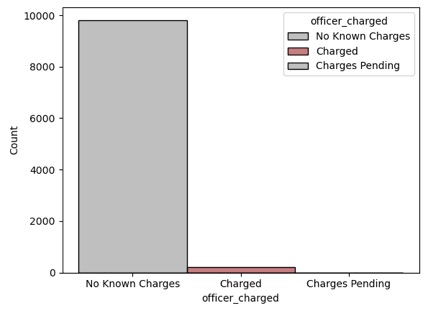

4.6: Charges Brought Against Police after Violent Encounters

Figure 6 seems to show another

problematic trend. As we’ve seen

earlier, around 20% of violent encounters were with unarmed individuals, and

around 20% of violent encounters involved people with apparent mental health

issues. But the number of charges

brought against officers involved in these violent encounters is closer to ~2%,

as seen in Figure 6. Note that not all

“Charged” officers were convicted, either.

Figure 6: Count of Charges Brought Against Officers After Violent Incidents

Just as a point to note, not all

officers involved in violent incidents necessarily need to be charged. Some police officers are put in intractable

situations where they need to make a difficult decision to protect others… after

all, it’s their job. But the proportion of

officers charged seems to be oddly small compared to the proportion of unarmed

people involved in violent incidents with those officers. That is the point of this figure.

Part 5: Conclusion

The question this project was trying to

answer is “what trends in use of force by police in the US appear to be

problematic?” with the intention of identifying the problems so that solution

could be formulated as a next step. The

visualizations in this report show clearly that police forces seem to have a

racial bias that expresses itself through younger black people experiencing

violence relative to other races.

Additionally, violent encounters with

mentally ill people seem to offer an avenue to reduce violent encounters by

improving quality and availability of mental health care and intervention. Violent encounters with unarmed individuals

seem to offer an even clearer path to reducing violent encounters by

intentionally avoiding use of excessive force.

Next, we saw a remarkable lack of hard

evidence in the form of recordings of violent encounters. Increasing use of police body cameras and

holding officers accountable for disabling cameras offers an opportunity to

ensure we hold all parties involved in a violent incident accountable to the

degree they were responsible for the aggression.

Finally, we saw a trend that very few officers involved in violent incidents are ever charged relative to the number of unarmed individuals involved in violent encounters every year. This discrepancy is concerning and could perhaps be mitigated by increasing use of body cameras and recording transparency.